By Katherine Brewer Ball

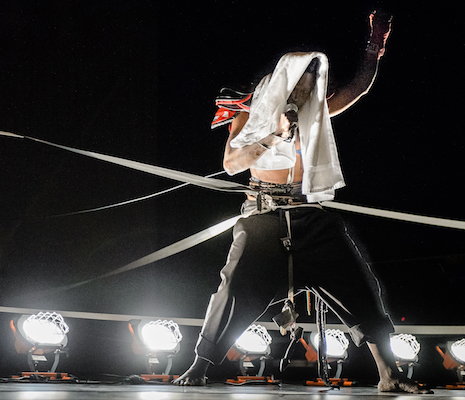

Fathers loom large in the works of Brooklyn-based artists Nora Chipaumire and Sacha Yanow. While the shape and weight varies in each artist’s piece, the figure of the father ghosts the bodies of both Chipaumire and Yanow as they inhabit the grand and dangerous space of the boxing ring and the family room. Chipaumire’s portrait of myself as my father

Chipaumire carries the speculative image of her father across the bodies, gestures, and languages of the three performers. Chipaumire tells us, “You can’t dismiss what happens to you physically as you sit in that space and you experience the work, or your journey with the work. There’s also what happens as the after-image or the after-sound. After you leave the physical space of the performance, the performance continues to be in conversation with your mind, your body, your pallet. I say I’m making work that is interested and invested very much in this thing of ‘how do you create an experience?’ and ‘how do you defy all these gazes?’” Superheroing the black man, Chipaumire’s gestural and sonic language continues working against Western visual regimes even after the performance is done.

In Sacha Yanow’s solo performance piece, Dad Band, she calls forth the figure of her ex-New Yorker father from his current home in Williamstown, Massachusetts. In conversation with artist Wynne Greenwood’s video-performance band Tracy and the Plastics, Yanow developed Dad Band as a portrait of her father, a sort of middle-class American Jewish dad archetype. She explains, “my dad is somebody who I have a pretty distant relationship with, or I did growing up. So I was thinking, how can I use this opportunity to band together with my dad and get to know him better? I started with the things that I sort of did know about him which were a lot of, like, his habits, his clothes, the shirts he likes, the shoes he likes, some of the music he likes, his Agatha Christie novels.” In the process of banding together with her father Yanow discovers the parts of him that she subconsciously reproduces, what she casually refers to as “the dad inside.” Yanow continues, “It's weird, like, how my dad's humor is a lot like my own lesbian humor, like the lesbians I know. I used to raid his closet for his flannels. That’s all he had. I would wear his jeans, his shirts. So there's something about that as part of, like, how I was understanding my own gender.” Performing the queer dad inside of her, Yanow sings her favorite dad songs, plays dress-up with his checkered shirts, and reads the newspaper; she crafts a loving and intimate image of the dad that she remembers, a dad that seems distant perhaps precisely because he is required to perform such an over-determined role. Finding her way into what feels like a hermetically sealed white patriarchal position, Yanow inhabits the versions of her dad-self that she both loves and resists. Dad Band is a love letter to every dad that holds himself at a distance, and a critique of all that is lost in such defensive and fearful stances.

The father is a heavy historical figure. Getting under the skin of the image machine, cross cut by the history of the West and colonialism. Chipaumire and Yanow create affective relations and speculative embodiments of their fathers. The father figure comes into focus just enough to see the shadows and forms it casts, even though, as Chipaumire reminds me, “not everything is legible to everybody.”